“Your Decision, My Decision, Our Decision”: A Principal’s Guide to Clarity and Vision in Decision-Making

Every day, school principals make dozens of decisions — from minor matters to choices that affect the entire school community (Decisions, Decisions! A Week in the Life of a Principal). With so many decisions, it’s critical for a principal to be crystal clear about who will make each decision and why.

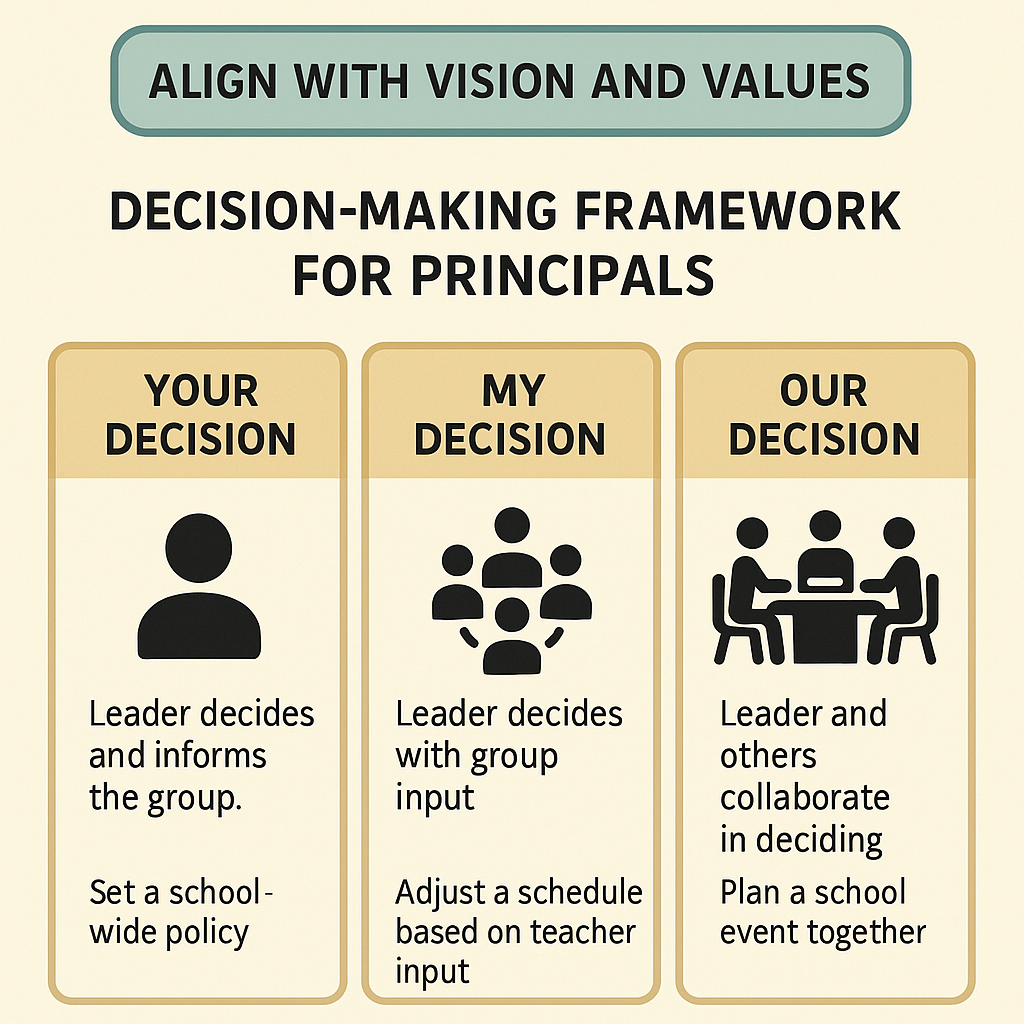

Is this a decision the principal will own (“my decision”), one that the team will develop together (“our decision”), or one that is delegated to staff or teachers (“your decision”)? At the same time, every decision should be anchored in the school’s vision and core values, so that even everyday choices move the school in the right direction (for more, see Why most reopening plans are doomed to fail).

The Need for Clarity in Decision Ownership

Clear decision ownership sets the stage for trust and effective action. When it’s ambiguous who gets to decide, teams can become frustrated or paralyzed. Principals should explicitly define who the decision-maker is in a given situation – whether it’s the principal alone, a collaborative group, or an individual staff member – to avoid confusion and false expectations. In practice, this means stating upfront how a decision will be made. For example, will the principal decide after input, will the leadership team vote, or will a teacher leader decide? As Liz Wiseman’s research highlights, effective leaders “clarify what needs to be addressed, why it’s important, and how decisions will be made” at the outset of a discussion (Multipliers by Liz Wiseman).

Such transparency prevents misunderstandings and builds buy-in. Seth Godin notes that “making good decisions with and for a group of people who believe us is called leadership” (At the speed of judgment) – in other words, true leadership involves both decisiveness and clear communication to those who trust you. By contrast, if a principal fails to declare who owns the decision and fails to state how the decision is tied to the vision of the school, they risk either making unilateral calls that leave others feeling disenfranchised or, conversely, delaying action because everyone assumed someone else would decide.

Clarity in decision roles is the foundation for both efficiency and trust.

“My Decision”: Leading When It Counts

Some decisions rightly fall squarely on the principal’s shoulders. In crisis situations, confidential personnel matters, or anytime a choice directly tied to legal or safety issues arises, the principal must step up and say, “I’ve got this one.” Communicating a “my decision” scenario means the principal takes full accountability. Leadership expert Stephen Covey often reminded leaders to “put first things first,” focusing on the most important priorities (Why most reopening plans are doomed to fail) – and sometimes the principal alone must decide on those high-stakes priorities.

Simon Rodberg, a former principal and author, underscores that you can’t shy away from this responsibility: “The school as a whole is counting on you to make decisions. That’s what leadership is: to decide where to go and, despite the difficulties, to move your school forward.” (Big Decisions Matter for Principals) In a “my decision” case, a principal still needs to ground the choice in the school’s vision and values and explain that context.

For example, if a principal decides to cancel a field trip due to lack of educational alignment, they need to have the courage to say: “I made this decision because it was not a great enough impact on student learning.”

Seth Godin warns that many leaders are “indoctrinated to let someone else take the wheel” when things get tough (At the speed of judgment), but an effective principal knows when they alone need to take the wheel. By confidently owning a tough call – and clearly saying “This is my decision and here’s why” – the principal provides direction and reassurance. Just as importantly, they model accountability.

As Rodberg puts it, “You have to decide. Even when it’s uncomfortable.” (Big Decisions Matter for Principals) “My decisions” are those where the principal leads decisively, communicates openly about the reasoning, and ensures the outcome aligns with the school’s vision.

“Your Decision”: Empowering Others through Delegation

No principal can—or should—make every decision. Effective leaders empower their teachers and staff by delegating appropriate decisions to them. “Your decision” means you (the teacher or staff member) have the authority to decide, and the principal will support and uphold your choice. Liz Wiseman describes this empowering approach as the “Investor” mindset: the leader gives ownership of a decision or project to someone else and “names a lead, giving them majority ownership (e.g., ‘51% of the vote’)” (Multipliers by Liz Wiseman).

The principal’s role then is to invest in that person’s success – providing guidance or resources as needed – but without undermining their ownership (Multipliers by Liz Wiseman). In practice, a principal might tell a teacher leader, “You’re closest to this issue, so it’s your decision how to adjust the schedule. Let me know what you decide and how I can help.”

Research supports this kind of trust: schools with more distributed decision-making tend to perform better. In fact, a landmark study by Leithwood and colleagues found that “collective leadership has a stronger influence on student learning than any individual source of leadership”, and in high-performing schools, teachers and others have greater influence in decisions. Notably, principals in those schools “do not lose influence as others gain it” – instead, effective principals encourage others to join in and share leadership.

By delegating, a principal multiplies the school’s leadership capacity. Liz Wiseman’s work similarly shows that “Multipliers” get far more from their teams than “Diminishers” because they trust others to figure things out (Multipliers by Liz Wiseman). When a principal hands off a decision, it sends a powerful message of trust and respect for the team’s professionalism. Of course, guardrails should be in place: the principal should ensure the person understands the school’s vision, any non-negotiables (e.g., budget limits or legal constraints), and the desired outcome. Stephen Covey would call this “stewardship delegation” – giving someone the what and why (the vision and goal), then letting them determine the how (Multipliers by Liz Wiseman). Done right, “your decision” delegation not only lightens the principal’s load but also develops leadership in others.

Teachers and staff feel a greater stake in the school’s direction, and decisions are often better because they’re made by those with on-the-ground insight. Finally, when delegating, the principal should publicly support the outcome. For example, if a department head makes a curricular decision, the principal backs it fully: “Mrs. Smith made this call, and I stand behind her decision.” This follow-through solidifies trust.

If the principal is not comfortable supporting the decision fully, then it’s not really a “your decision.”

Empowering others to decide on “your decision” matters builds capacity, ownership, and often better results – all while keeping decisions aligned with the shared vision through clear initial guidelines.

“Our Decision”: Collaborating for Consensus and Buy-In

Many school decisions are best made together. “Our decision” denotes a collaborative process – the principal and stakeholders (teachers, parents, students, or the community) work jointly to reach a conclusion. This is appropriate for decisions that benefit from diverse perspectives or will affect many people (for example, developing a new school mission statement, adopting a curriculum, or setting school policies). Collaboration not only taps into collective wisdom but also generates buy-in that smooths implementation.

Stephen Covey’s Habit 6, “Synergize,” captures this idea: by valuing differences and brainstorming together, teams can arrive at creative solutions superior to any one person’s idea. In practical terms, an “our decision” approach might involve forming a committee or running a staff consultation. The principal’s job here is to facilitate the process and ensure it stays aligned with the school’s vision.

One key to success is clarity about the decision process (again, no ambiguity!). Liz Wiseman describes great collaborative leaders as “Debate Makers” who “frame the issue, define the right team, gather the data, and clarify why the issue is important and how the decision will be made” (Multipliers by Liz Wiseman) before the discussion even begins. For instance, a principal might convene a task force and say, “We’ll discuss options and by the end of today’s meeting, we as a group will come to a consensus – that will be our decision to carry forward.”

It’s important to note here that “our decision” does not mean it has to take forever to make a decision. You can gather the right people and make it happen in a short five-minute meeting.

During the collaboration, effective principals create a safe environment for honest dialogue (no retribution for dissenting opinions) and keep the conversation focused on facts and the school’s goals (Multipliers by Liz Wiseman). By encouraging “all points of view” and tough questions, the group can hammer out the best solution (Multipliers by Liz Wiseman).

If consensus can’t be reached, the principal might guide the group to majority vote or make the final call on the group’s behalf, but in either case everyone should know the method in advance. It’s not uncommon for a principal to start making it “our decision” and then realize part-way through that it needs to be a “my decision” instead. It’s not the end of the world, but it will likely result in frustration.

Teachers who feel genuinely involved in decisions show higher morale and commitment, and schools with broad stakeholder input tend to be more successful. Importantly, sharing decisions doesn’t weaken the principal’s authority – it strengthens the school. High-performing schools have “fatter” decision-making structures (more people involved) and yet the principal’s influence is not diminished by this inclusivity.

In fact, the principal’s role as a visionary facilitator becomes more vital. When “our decisions” are made, people are more likely to fully support them because they helped shape them. To illustrate, imagine a team of teachers collaboratively deciding on a new report card format that better reflects student skills. If they conclude together after rigorous discussion, they all understand the rationale and feel ownership; when it’s rolled out, they champion it to students and parents.

This is far more effective than a top-down edict. In summary, “our decision” approaches leverage the collective insight of the community and build strong buy-in. The principal leads by convening, guiding toward alignment with the vision, and then standing as one with the group’s decision.

Aligning Every Decision with Vision and Values

No matter who is making the call, every decision in a school should serve the school’s overarching vision and core values. This alignment is the compass that keeps the school on course.

Stephen Covey’s famous “big rocks” metaphor: the big, important things (like the school’s mission, student wellbeing, and learning goals) must go into the plan first, before the smaller pebbles and sand (Why most reopening plans are doomed to fail).

In a leadership context, that means principals should continuously ask, “What do we really need to focus on? What really matters in our school?”. If a potential action doesn’t align with those “big rocks” – the core priorities – then it’s likely a distraction. “If you don’t have [your big rocks identified], then all your little plans mean absolutely nothing.” (Why most reopening plans are doomed to fail)

In practice, aligning decisions with values might look like this: before deciding, the principal (or team) explicitly connects the issue to the school’s vision. For example, if the school’s vision emphasizes equity, a principal might frame a budget decision in terms of equity (“How does each option impact equity in our school?”) to ensure the choice upholds that value. Stephen Covey’s “Begin with the End in Mind” habit is also relevant – starting any initiative by envisioning the desired outcome (which should tie into the school’s mission).

When decisions are consistently filtered through the lens of vision and values, the cumulative effect is powerful: the school community sees that the leadership “walks the talk,” and trust grows. Moreover, having clear values actually speeds up decision-making; as Roy Disney famously said, “When your values are clear, your decisions are easy.” (Inc.)

For principals, this means that a well-defined school vision and a collaboratively developed set of core values become a north star, which always tells you where you are. They guide not only big strategic decisions but also everyday choices – from hiring staff (are we hiring people who embody our values?) to discipline policies (do our responses to misbehavior consistently reflect our values?).

One strategy is to make the vision visible: literally post the vision statement and values in meeting rooms and frequently reference them when discussing options. By doing so, aligning with the vision becomes habit. For instance, a principal might voice during a meeting, “Our core value of ‘whole-child development’ tells me we should choose the after-school program that best supports students’ social-emotional growth.”

Alignment also means being willing to say no to ideas that are exciting but off-mission. Covey’s principle-centered leadership approach would have us prioritize what matters most and exercise discipline to not get scattered. Keeping decisions tethered to vision and values ensures coherence in school direction. It helps avoid the “shiny object syndrome” of chasing trendy programs that don’t fit the school’s identity. Instead, the principal and school team channel their limited time and energy into actions that truly advance the shared vision. This consistency not only drives better results but also models integrity for students and staff.

Communicating Decisions and Ownership Clearly

Even the best decision won’t get far if it isn’t communicated well. Once a decision is made – whether by you, me, or us – it’s crucial to close the loop with clear communication to all affected parties. Principals should announce what was decided and why, and do so in a timely, transparent manner. Leadership experts universally stress this communication piece.

After facilitating robust debate, Liz Wiseman notes that effective leaders “communicate the decision and [the] rationale” so people understand the reasoning (Multipliers by Liz Wiseman). This step is essential for maintaining trust, especially in collaborative or delegated decisions. If teachers contributed to an “our decision,” they want to hear how their input influenced the outcome. If a decision was “yours” (delegated), the principal should help broadcast it, giving credit to the decision-maker. For example, “At yesterday’s curriculum council, our team decided X in line with our school goals, and here’s the thinking behind it…” By explaining the why, the principal affirms that the decision was grounded in vision and data, not whim.

Clear communication also involves outlining any next steps or expectations now that the decision is made. In a sense, this is about ensuring execution: everyone should know their role moving forward. Additionally, when communicating a decision, it’s helpful to reference back to who owned the decision, reinforcing the framework. One might say, “This was our decision as a staff, and together we chose this path,” or “I made this decision (a my decision) after consulting all of you, because I believe it’s in the best interest of our students.” Such statements reinforce the decision-making model and show that it was a conscious choice, not a lapse into autocracy or an abdication of leadership.

It’s also important to be consistent: if you promised a group process, don’t suddenly flip it to a principal-only decision without explanation, and vice versa. Any changes in the process should themselves be communicated with clear reasoning.

By being transparent about both process and outcome, principals cultivate an atmosphere of respect and predictability. Over time, teachers and parents come to know what to expect: they’ll know which kinds of decisions they’ll be consulted on, which decisions the principal will just make, and where they have autonomy.

This clarity can dramatically reduce anxiety and second-guessing in a school’s culture. As Tom Hoerr quipped, “Few decisions (important ones, anyway) should be the principal’s alone. Teachers have specialized knowledge… that can inform better decisions.” (Principal Connection / Four Tips on Leading Adults) When people know their voices will be heard and how decisions will unfold, they can focus energy on implementation rather than office politics. Finally, good communication includes listening.

After announcing a decision, a principal should be open to questions and be willing to reiterate how the decision aligns with the school’s values and vision (since repetition of the vision helps keep everyone aligned). This follow-through completes the decision cycle: from clarifying ownership at the start, to aligning with vision during deliberation, to communicating clearly at the end. It’s a loop of accountability and learning. Every well-communicated decision builds credibility for the principal and confidence in the school’s direction.

Conclusion

In the complex environment of a school, principled and clear decision-making is one of a principal’s greatest tools. By explicitly signaling who owns each decision – “your decision,” “my decision,” or “our decision” – a principal sets the stage for transparency and collaboration.

And by relentlessly tying decisions back to the school’s vision and values, a leader ensures that every choice, big or small, drives the school toward its ultimate goals. This approach requires intentional communication and a bit of courage, but the payoff is enormous: better decisions, a stronger team, and a school culture where everyone knows where we’re headed and feels invested in getting there.

A principal who masters the art of decision clarity and vision alignment doesn’t just make decisions faster or easier – they build a united school community that trusts those decisions and works together to turn them into reality.

Notes mentioning this note

There are no notes linking to this note.